What Kind of Performance Art Does Tin Pan Alley Perfor

Coordinates: 40°44′44″N 73°59′22.5″Westward / 40.74556°Northward 73.989583°Due west / 40.74556; -73.989583

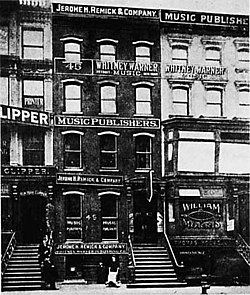

Buildings of Can Pan Aisle, 1910[i]

The same buildings, 2011

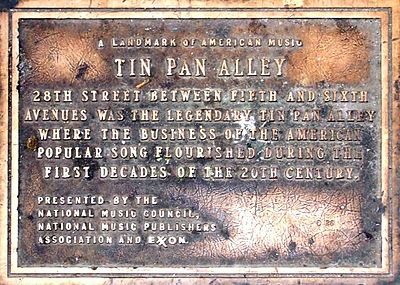

Tin Pan Alley was a collection of music publishers and songwriters in New York City which dominated the popular music of the United States in the belatedly 19th and early on 20th centuries. It originally referred to a specific place: W 28th Street between Fifth and 6th Avenues in the Flower District[2] of Manhattan; a plaque (see below) on the sidewalk on 28th Street betwixt Broadway and Sixth commemorates information technology.[three] [4] [5] [6]

In 2019, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission took upward the question of preserving 5 buildings on the due north side of the street as a Tin Pan Alley Historic District.[vii] The agency designated five buildings (47–55 West 28th Street) private landmarks on December ten, 2019, after a concerted effort by the "Save Can Pan Alley" initiative of the 29th Street Neighborhood Clan.[8] Following successful protection of these landmarks, projection director George Calderaro and other proponents formed the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project to continue and commemorate the legacy of Tin can Pan Aisle with various advocacy and educational activities.

On April 2, 2022, 28th Street between Broadway and 6th Avenue was officially co-named "Tin Pan Alley" by the City of New York in a celebration featuring NYC City Councilmember Erik Bottcher, Manhattan Civic President Mark Levine and representatives from the NYC Landmarks Preservation Committee, the Flatiron/23rd Street Partnership and the Tin can Pan Alley American Popular Music Project which advocated for the co-naming.

The get-go of Tin Pan Aisle is ordinarily dated to about 1885, when a number of music publishers set up store in the same district of Manhattan. The end of Tin Pan Alley is less clear cutting. Some date it to the outset of the Great Depression in the 1930s when the phonograph, radio, and motion pictures supplanted canvas music equally the driving force of American popular music, while others consider Tin Pan Alley to accept continued into the 1950s when earlier styles of music were upstaged by the rise of rock & curlicue, which was centered on the Brill Building. Brill Edifice songwriter Neil Sedaka described his employer as being a natural outgrowth of Tin Pan Alley, in that the older songwriters were withal employed in Tin Pan Alley firms while younger songwriters such as Sedaka found work at the Brill Edifice.[9]

Origin of the proper noun [edit]

Various explanations have been advanced to account for the origins of the term "Can Pan Alley". The nigh pop business relationship holds that it was originally a derogatory reference by Monroe H. Rosenfeld in the New York Herald to the commonage sound made by many "inexpensive upright pianos" all playing different tunes being reminiscent of the banging of tin pans in an alleyway.[10] [eleven] However, no article by Rosenfeld that uses the term has been establish.[12] [thirteen]

Simon Napier-Bell quotes an account of the origin of the name published in a 1930 book most the music business organisation. In this version, popular songwriter Harry von Tilzer was being interviewed about the area around 28th Street and 5th Avenue, where many music publishers had offices. Von Tilzer had modified his expensive Kindler & Collins piano past placing strips of paper downward the strings to give the instrument a more percussive sound. The journalist told von Tilzer, "Your Kindler & Collins sounds exactly similar a can can. I'll call the article 'Tin Pan Alley'."[14] In whatsoever case, the name was firmly attached by the autumn of 1908, when The Hampton Magazine published an article titled "Tin Pan Alley" about 28th Street.[15]

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, "tin pan" was slang for "a decrepit piano" (1882), and the term came to mean a "hit song writing concern" by 1907.[16]

With time, the nickname came to depict the American music publishing manufacture in general.[xi] The term then spread to the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, where "Tin Pan Alley" is as well used to describe Kingdom of denmark Street in London'due south W Finish.[17] In the 1920s the street became known as "Britain'due south Tin can Pan Alley" because of its large number of music shops.[eighteen]

These buildings (47–55 West 28th Street) and others on Due west 28th Street between Sixth Avenue and Broadway in Manhattan housed the canvas-music publishers that were the center of American popular music in the early 20th century. The buildings shown were designated as historic landmarks in 2019.

Origin of song publishing in New York City [edit]

In the mid-19th century, copyright control of melodies was not as strict, and publishers would ofttimes print their own versions of the songs popular at the time. With stronger copyright protection laws tardily in the century, songwriters, composers, lyricists, and publishers started working together for their mutual financial benefit. Songwriters would literally bang on the doors of Tin Pan Alley businesses to go new textile.

The commercial eye of the popular music publishing industry changed during the course of the 19th century, starting in Boston and moving to Philadelphia, Chicago and Cincinnati earlier settling in New York City under the influence of new and vigorous publishers which full-bodied on vocal music. The two virtually enterprising New York publishers were Willis Woodard and T.B. Harms, the offset companies to specialize in popular songs rather than hymns or classical music.[xix] Naturally, these firms were located in the entertainment district, which, at the time, was centered on Union Square. Witmark was the get-go publishing business firm to motility to West 28th Street every bit the amusement district gradually shifted uptown, and past the late 1890s about publishers had followed their lead.[eleven]

The biggest music houses established themselves in New York City, but small-scale local publishers – often connected with commercial printers or music stores – continued to flourish throughout the country, and there were of import regional music publishing centers in Chicago, New Orleans, St. Louis, and Boston. When a tune became a significant local striking, rights to it were usually purchased from the local publisher by one of the big New York firms.

In its prime [edit]

"I'one thousand a Yiddish Cowboy" (1908)

The song publishers who created Tin Pan Alley frequently had backgrounds equally salesmen. Isadore Witmark previously sold water filters and Leo Feist had sold corsets. Joe Stern and Edward B. Marks had sold neckties and buttons, respectively.[20] The music houses in lower Manhattan were lively places, with a steady stream of songwriters, vaudeville and Broadway performers, musicians, and "song pluggers" coming and going.

Aspiring songwriters came to demonstrate tunes they hoped to sell. When tunes were purchased from unknowns with no previous hits, the proper noun of someone with the business firm was often added every bit co-composer (in order to keep a higher pct of royalties within the firm), or all rights to the song were purchased outright for a flat fee (including rights to put someone else'south proper noun on the canvas music equally the composer). An extraordinary number of Jewish East European immigrants became the music publishers and songwriters on Can Pan Alley – the about famous being Irving Berlin. Songwriters who became established producers of successful songs were hired to exist on the staff of the music houses.

"Vocal pluggers" were pianists and singers who represented the music publishers, making their living demonstrating songs to promote sales of sheet music. Most music stores had song pluggers on staff. Other pluggers were employed by the publishers to travel and familiarize the public with their new publications. Amongst the ranks of song pluggers were George Gershwin, Harry Warren, Vincent Youmans and Al Sherman. A more aggressive form of song plugging was known as "booming": it meant buying dozens of tickets for shows, infiltrating the audience and and so singing the song to be plugged. At Shapiro Bernstein, Louis Bernstein recalled taking his plugging crew to cycle races at Madison Foursquare Garden: "They had 20,000 people at that place, we had a pianist and a vocalist with a large horn. We'd sing a song to them thirty times a night. They'd cheer and yell, and nosotros kept pounding away at them. When people walked out, they'd exist singing the song. They couldn't help it."[21]

When vaudeville performers played New York City, they would often visit various Can Pan Alley firms to find new songs for their acts. Second- and tertiary-rate performers oftentimes paid for rights to utilize a new song, while famous stars were given free copies of publisher's new numbers or were paid to perform them, the publishers knowing this was valuable advertisement.

Initially Tin Pan Alley specialized in melodramatic ballads and comic novelty songs, but it embraced the newly pop styles of the cakewalk and ragtime music. Later, jazz and dejection were incorporated, although less completely, as Can Pan Alley was oriented towards producing songs that amateur singers or pocket-sized town bands could perform from printed music. In the 1910s and 1920s Tin Pan Alley published pop songs and dance numbers created in newly popular jazz and dejection styles.

Plaque commemorating Tin Pan Alley

Influence on law and business organisation [edit]

A grouping of Tin can Pan Aisle music houses formed the Music Publishers Clan of the Us on June 11, 1895, and unsuccessfully lobbied the federal government in favor of the Treloar Copyright Bill, which would accept changed the term of copyright for published music from 24 to 40 years, renewable for an additional 20 instead of fourteen years. The beak, if enacted, would also have included music among the field of study matter covered past the Manufacturing clause of the International Copyright Human activity of 1891.

The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) was founded in 1914 to assist and protect the interests of established publishers and composers. New members were only admitted with sponsorship of existing members.

The term and established business organization methodologies associated with Can Pan Alley persisted into the 1960s when innovative artists like Bob Dylan helped establish new norms. Referring to the dominant conventions of music publishers of the early 20th century, "Tin Pan Aisle is gone," Bob Dylan proclaimed in 1985, "I put an end to it. People can tape their own songs now."[22]

Contributions to World War II [edit]

During the Second World War, Tin Pan Alley and the federal government teamed upward to produce a war vocal that would inspire the American public to back up the fight against the Axis, something they both "seemed to believe ... was vital to the war effort".[23] The Office of State of war Information was in charge of this projection, and believed that Tin Pan Alley contained "a reservoir of talent and competence capable of influencing people's feelings and opinions" that it "might be capable of even greater influence during wartime than that of George One thousand. Cohan's 'Over There' during World State of war I."[23] In the Us, the song "Over There" has been said to be the most popular and resonant patriotic song associated with World War I.[23] Due to the large fan base of Tin can Pan Alley, the authorities believed that this sector of the music business organisation would be far-reaching in spreading patriotic sentiments.[23]

In the United states Congress, congressmen quarreled over a proposal to exempt musicians and other entertainers from the draft in order to remain in the country to heave morale.[23] Stateside, these artists and performers were continuously using bachelor media to promote the war endeavour and to demonstrate a commitment to victory.[24] Withal, the proposal was contested by those who strongly believed that merely those who provided more substantial contributions to the war attempt should benefit from whatsoever draft legislation.[23]

As the state of war progressed, those in charge of writing the would-be national state of war song began to understand that the involvement of the public lay elsewhere. Since the music would have upwards such a large amount of airtime, it was imperative that the writing be consistent with the war message that the radio was carrying throughout the nation. In her book, God Bless America: Tin Pan Alley Goes to State of war, Kathleen East. R. Smith writes that "escapism seemed to be a high priority for music listeners", leading "the composers of Tin can Pan Alley [to struggle] to write a state of war vocal that would entreatment both to civilians and the armed forces".[23] By the stop of the state of war, no such vocal had been produced that could rival hits like "Over There" from World War I.[23]

Whether or non the number of songs circulated from Tin Pan Aisle betwixt 1939 and 1945 was greater than during the First Globe War is still debated. In his volume The Songs That Fought the State of war: Popular Music and the Habitation Front end, John Bush Jones cites Jeffrey C. Livingstone equally claiming that Can Pan Aisle released more songs during World War I than it did in World War II.[25] Jones, on the other manus, argues that "at that place is too strong documentary evidence that the output of American war-related songs during Earth War Ii was almost probably unsurpassed in any other war".[25]

Composers and lyricists [edit]

Leading Tin Pan Aisle composers and lyricists include:

- Milton Ager

- Thomas Southward. Allen

- Harold Arlen

- Ernest Ball

- Irving Berlin

- Bernard Bierman

- George Botsford

- Shelton Brooks

- Lew Brown

- Nacio Herb Chocolate-brown

- Irving Caesar

- Sammy Cahn

- Hoagy Carmichael

- George M. Cohan

- Con Conrad

- J. Fred Coots

- Gussie Lord Davis

- Buddy DeSylva

- Walter Donaldson

- Paul Dresser

- Dave Dreyer

- Al Dubin

- Vernon Duke

- Dorothy Fields

- Ted Fio Rito

- Max Freedman

- Cliff Friend

- George Gershwin

- Ira Gershwin

- Oscar Hammerstein II

- E. Y. "Yip" Harburg

- Charles K. Harris

- Lorenz Hart

- Ray Henderson

- James P. Johnson

- Isham Jones

- Scott Joplin

- Gus Kahn

- Bert Kalmar

- Jerome Kern

- Ted Koehler

- Al Lewis

- Sam G. Lewis

- Frank Loesser

- Jimmy McHugh

- F. Due west. Meacham

- Johnny Mercer

- Halsey K. Mohr

- Theodora Morse

- Ethelbert Nevin

- Mitchell Parish

- Bernice Petkere

- Maceo Pinkard

- Lew Pollack

- Cole Porter

- Andy Razaf

- Richard Rodgers

- Harry Scarlet

- Al Sherman

- Lou Singer[26]

- Sunny Skylar

- Ted Snyder

- Kay Swift

- Edward Teschemacher

- Albert Von Tilzer

- Harry Von Tilzer

- Fats Waller

- Harry Warren

- Richard A. Whiting

- Harry One thousand. Woods

- Allie Wrubel

- Jack Yellen

- Vincent Youmans

- Joe Young

- Hy Zaret[26]

Notable hitting songs [edit]

Tin Pan Alley's biggest hits included:

- "A Bird in a Gilded Cage" (Harry Von Tilzer, 1900)

- "Subsequently the Brawl" (Charles K. Harris, 1892)

- "Own't She Sugariness" (Jack Yellen and Milton Ager, 1927)

- "Alabama Jubilee" (Jack Yellen and George L. Cobb, 1915)

- "Alexander's Ragtime Band" (Irving Berlin, 1911)

- "All Alone" (Irving Berlin, 1924)

- "At a Georgia Campmeeting" (Kerry Mills, 1897)

- "Baby Face" (Benny Davis and Harry Akst, 1926)

- "Bill Bailey, Won't You Please Come Home" (Huey Cannon, 1902)

- "By the Light of the Argent Moon" (Gus Edwards and Edward Madden, 1909)

- "Carolina in the Morning" (Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson, 1922)

- "Come Josephine in My Flying Machine" (Fred Fisher and Alfred Bryan, 1910)

- "Down by the One-time Mill Stream" (Tell Taylor, 1910)

- "Everybody Loves My Baby" (Spencer Williams, 1924)

- "For Sentimental Reasons" (Al Sherman, Abner Silvery and Edward Heyman, 1936)

- "Requite My Regards to Broadway" (George M. Cohan, 1904)

- "God Bless America" (Irving Berlin, 1918; revised 1938)

- "Happy Days Are Hither Again" (Jack Yellen and Milton Ager, 1930)

- "Hearts and Flowers" (Theodore Moses Tobani, 1899)

- "Hullo Ma Babe (Hi Ma Ragtime Gal)" (Emerson, Howard, and Sterling, 1899)

- "I Cried for You" (Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Dark-brown, 1923)

- "I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles" (John Kellette, 1919)

- "In the Baggage Bus Ahead" (Gussie L. Davis, 1896)

- "In the Practiced Quondam Summer Time" (Ren Shields and George Evans, 1902)

- "In the Shade of the Former Apple Tree" (Harry Williams and Egbert van Alstyne, 1905)

- "G-Thou-K-Katy" (Geoffrey O'Hara, 1918)

- "Allow Me Call You Sweetheart" (Beth Slater Whitson and Leo Friedman, 1910)

- "Lindbergh (The Eagle of the U.S.A.)" (Al Sherman and Howard Johnson, 1927)

- "Lovesick Blues" (Cliff Friend and Irving Mills, 1922)

- "Mighty Lak' a Rose" (Ethelbert Nevin & Frank L. Stanton, 1901)

- "Mister Johnson, Turn Me Loose" (Ben Harney, 1896)

- "My Blue Heaven" (Walter Donaldson and George Whiting, 1927)

- "Now's the Fourth dimension to Fall in Beloved" (Al Sherman and Al Lewis, 1931)

- "Oh, Donna Clara" (Irving Caesar, 1928)

- "Oh by Jingo!" (Albert Von Tilzer, 1919)

- "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Abroad" (Paul Dresser 1897)

- "Over There" (George Thousand. Cohan, 1917)

- "Peg o' My Heart" (Fred Fisher and Alfred Bryan, 1913)

- "Polish Little Glow Worm" (Paul Lincke and Lilla Cayley Robinson, 1907)

- "Shine on Harvest Moon" (Nora Bayes and Jack Norworth, 1908)

- "Some of These Days" (Shelton Brooks, 1911)

- "Stardust" (Hoagy Carmichael and Mitchell Parish, 1927)

- "Swanee" (George Gershwin, 1919)

- "Sweet Georgia Brown" (Maceo Pinkard, 1925)

- "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" (Albert Von Tilzer, 1908)

- "The Ring Played On" (Charles B. Ward and John F. Palmer, 1895)

- "The Darktown Strutters' Ball" (Shelton Brooks, 1917)

- "The Little Lost Child" (Marks and Stern, 1894)

- "The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo" (Charles Coborn, 1892)

- "The Sidewalks of New York" (Lawlor and Blake, 1894)

- "The Japanese Sandman" (1920)

- "In that location'll Be a Hot Time in the Former Boondocks Tonight" (Joe Hayden and Theodore Mertz, 1896)

- "Warmest Baby in the Bunch" (George M. Cohan, 1896)

- "Manner Downward Yonder in New Orleans" (Creamer and Turner Layton, 1922)

- "Whispering" (1920)

- "Yes, Nosotros Have No Bananas" (Frank Silver and Irving Cohn, 1923)

- "Y'all Gotta Be a Football Hero" (Al Sherman, Buddy Fields and Al Lewis, 1933)

In pop civilisation [edit]

- In the 1959–1960 television set season, NBC aired a sitcom Dearest and Matrimony, based on the fictitious William Harris Music Publishing Company set in Tin Pan Alley. William Demarest, Stubby Kaye, Jeanne Bal, and Murray Hamilton co-starred in the series, which aired 18 episodes.

- In the song "Bob Dylan's Blues" from Bob Dylan's 1963 anthology The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, he introduces the song, saying, "Unlike about of the songs nowadays that take been written up town in Can Pan Alley, that'southward where most of the folk songs come from nowadays, this, this is a song, this wasn't written upward there, this was written down somewhere in the Usa."

- In the song "Biting Fingers" from the 1975 autobiographical concept album Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy, Elton John refers to himself and his longtime songwriting partner, lyricist Bernie Taupin, every bit the "Can Pan Alley Twins".

- Neil Diamond's liner notes ("... tin can pan aisle died hard, simply there was always the music to keep yous going ...") indicate that the album Cute Noise (1976) was intended every bit a tribute to his days at that place.

- Tin can Pan Alley is mentioned in the song "It Never Rains" (1982) past Dire Straits.

- The Bob Geddins dejection vocal "Can Pan Alley (aka The Roughest Identify in Town)", recorded by Jimmy Wilson, was a top 10 hit on the R&B chart in 1953[27] and became a popular song amongst West Coast blues performers.[28] The song was likewise covered by Stevie Ray Vaughan.

- The song "Tin Pan Alley" past The Apples in Stereo.

- Tin Pan Aisle of the 1960s was discussed by Robbie Robertson of The Band in the Martin Scorsese picture show of The Ring's final concert in 1976, The Last Waltz.

- In the 1970s to early 1980s, a Times Square bar named Tin Pan Alley, its owners, Steve d'Agroso and Maggie Smith, and many of its patrons were the real-life inspiration for the HBO series The Deuce. The bar was renamed The Hi-Chapeau in the serial.[29]

- The vocal "Who Are You" past The Who has the stanza "I stretched back and I hiccupped / And looked back on my decorated day / Eleven hours in the Can Pan / God, there'south got to be another mode", which references a long legal meeting with music publisher Allen Klein.[thirty] [31] [32]

- In Soul Music past Terry Pratchett, in which rock and roll music is introduced to the magical, medieval Discworld, Tin Lid Alley in Ankh-Morpork is the location of the Guild of Musicians which effectively operates as a protection noise, charging new members $75 for admission and brutally clamping downwardly on unlicensed musicians.

Come across also [edit]

- Music Row

- Printer'south Alley

- Radio Row

- The Tin Pan Alley Rag

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ Reublin, Rick (March 2009) "America'due south Music Publishing Manufacture: The story of Tin Pan Alley" The Parlor Songs Academy

- ^ Dickerson, Aitlin (March 12, 2013) "'Bowery Boys' Are Apprentice But Beloved New York Historians" NPR

- ^ Mooney Jake (October 17, 2008) "City Room: Tin Pan Alley, Not So Pretty" The New York Times

- ^ Gray, Christpher (July thirteen, 2003) "Streetscapes: West 28th Street, Broadway to 6th; A Tin Pan Alley, Chockablock With Life, if Not Vocal" The New York Times

- ^ Spencer, Luke J. (ndg) "The Remnants of Tin Pan Aisle" Atlas Obscura

- ^ Miller, Tom (April 8, 2016) "A Tin Pan Alley Survivor -- No. 38 West 28th Street " Daytonian in Manhattan

- ^ "Manhattan'southward Tin Pan Alley could get a city landmark". am New York . Retrieved March eighteen, 2019.

- ^ Staff (December 10, 2019) "LPC Designates 5 Historic Buildings Associated with Tin Pan Alley" (press release) New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee

- ^ Today's Mini-Concert - 4/14/2021

- ^ Charlton (2011), p.three Quote: the "term Tin Pan Alley referred to the thin, tinny tone quality of cheap upright pianos used in music publisher's offices."

- ^ a b c Hamm (1983), p.341

- ^ Friedmann, Jonathan Fifty. (2018). Musical Aesthetics: An Introduction to Concepts, Theories, and Functions. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 119.

- ^ Brackett, David (2005). The Pop, Rock, and Soul Reader: Histories and Debates. Irvington, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN0195125711. [ page needed ]

- ^ Naper-Bong, Simon, Ta-ra-ra-Boom-de-ay: The Beginning of the Music Business, (2014), p.7: quoted from Goldberg, Isaac and George Gershwin, Tin Pan Alley: A Chronicle of the American Popular Music Racket, (1930)

- ^ Browne, Porter Emerson (October 1908) "Tin Pan Alley" The Hampton Mag v.21, n.4, pp.455-462

- ^ "tin pan aisle" etyomonline.com, January 14, 2020

- ^ Daley, Dan (Jan 8, 2004). "Pop'due south street of dreams". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

"Nosotros used to think of Tin can Pan Alley, which is what they called Denmark Street years ago when all the music publishers were there, every bit rather old-fashioned," recalls Peter Asher

- ^ "Tin can Pan Aisle (London)", musicpilgrimages.com, November seven, 2009

- ^ Hischak, Thomas Southward. (ndg) "Can Pan Alley" on Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online/Oxford University Printing

- ^ Whitcomb, Ian (1973) After the Ball. Allen Lane, p.44

- ^ Naper-Bell, Simon, Ta-ra-ra-Boom-de-ay: The Beginning of the Music Business concern, (2014), p.6

- ^ Dwyer, Colin (October 13, 2016). "Bob Dylan, Titan Of American Music, Wins 2016 Nobel Prize In Literature". NPR.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h Smith, Kathleen Eastward. R. (2003). God Bless America: Tin can Pan Alley Goes to War. Lexington, Kentucky: Academy Press of Kentucky. pp. ii–6

- ^ Hajduk, John (Dec 2003). "Tin Pan Alley on the March: Popular Music, World War 2, and the Quest for a Bang-up War Vocal". Popular Music and Society. 26 (iv): 497–512. doi:ten.1080/0300776032000144940. S2CID 194077544.

- ^ a b John Bush Jones, God Bless America: Tin Pan Aisle Goes to War (Lebanon: University Press of Kentucky, 2003), pp. 32–33

- ^ a b "Song for Hard Times", Harvard Magazine, May–June 2009

- ^ Santelli, Robert (2001). Penguin Books, p. 524

- ^ Herzhaft, Gérard (1992). Encyclopedia of the Blues. University of Arkansas Printing, p. 475

- ^ "The Deuce: Backside the Scenes Podcast 72". The Rialto Study. September 3, 2017. Retrieved Jan 5, 2019.

- ^ Perrone, Pierre (October 23, 2011) "Allen Klein: Notorious concern manager for the Beatles and the Rolling Stones" The Contained

- ^ Rosenbaum, Marty (May 21, 2019) "The True Meanings Behind The Who's Virtually Famous Songs: Who Are You" 93XRT

- ^ Spray, Angie (February eleven, 2015) "Who Are You and Moon'southward death" Rockapedia

Bibliography

- Blossom, Ken. The American Songbook: The Singers, the Songwriters, and the Songs. New York: Black Domestic dog and Leventhal, 2005. ISBN 1-57912-448-8 OCLC 62411478

- Charlton, Katherine (2011). Rock music manner: a history. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Forte, Allen. Listening to Classic American Pop Songs. New Oasis: Yale University Printing, 2001.

- Furia, Philip (1990). The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America's Not bad Lyricists. ISBN0-19-507473-4. .

- Furia, Philip; Lasser, Michael (2006). The American's Songs: The Stories Behind the Songs of Broadway, Hollywood, and Tin Pan Alley. ISBN0-415-99052-1. .

- Goldberg, Isaac. Tin Pan Aisle, A Relate of American Music. New York: Frederick Ungar, [1930], 1961.

- Hajduk, John C. "Tin Pan Aisle on the March: Popular Music, World War II, and the Quest for a Great War Song." Popular Music and Society 26.iv (2003): 497–512.

- Hamm, Charles. Music in the New Globe. New York: Norton, 1983. ISBN 0-393-95193-vi

- Jasen, David A. Tin Pan Aisle: The Composers, the Songs, the Performers and Their Times. New York: Donald I. Fine, Primus, 1988. ISBN one-55611-099-5 OCLC 18135644

- Jasen, David A., and Gene Jones. Spreadin' Rhythm Around: Blackness Popular Songwriters, 1880–1930. New York: Schirmer Books, 1998.

- Jones, John Bush (2015). Reinventing Dixie: Tin Pan Alley'southward Songs and the Cosmos of the Mythic South. Louisiana Country Academy Printing. ISBN9780807159446. OCLC 894313622.

- Marks, Edward B., as told to Abbott J. Liebling. They All Sang: From Tony Pastor to Rudy Vallée. New York: Viking Press, 1934.

- Morath, Max. The NPR Curious Listener's Guide to Popular Standards. New York: Penguin Putnam, Berkley Publishing, a Perigree Book, 2002. ISBN 0399527443

- Napier-Bell, Simon (2014). Ta-ra-ra-Blast-de-ay: The Starting time of the Music Business. ISBN978-i-78352-031-2.

- Sanjek, Russell. American Popular Music and Its Business organisation: The First Four Hundred Years, Volume III, From 1900 to 1984. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Sanjek, Russell. From Print to Plastic: Publishing and Promoting America'southward Pop Music, 1900–1980. I.S.A.K. Monographs: Number 20. Brooklyn: Institute for Studies in American Music, Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College, City Academy of New York, 1983.

- Smith, Kathleen Eastward. R. God Bless America: Tin Pan Alley Goes to War. Lexington, Ky: University Press of Kentucky, 2003. ISBN 0-8131-2256-2 OCLC 50868277

- Tawa, Nicholas E. The Way to Can Pan Alley: American Pop Vocal, 1866–1910. New York: Schirmer Books, 1990. ISBN 0028725417

- Whitcomb, Ian After the Brawl: Pop Music from Rag to Rock. New York: Proscenium Publishers, 1986, reprint of Penguin Printing, 1972. ISBN 0-671-21468-iii OCLC 628022

- Wilder, Alec. American Pop Song: The Great Innovators, 1900–1950. London: Oxford University Press, 1972.

- Zinsser, William. Easy to Call back: The Slap-up American Songwriters and Their Songs. Jaffrey, NH: David R. Godine, 2000. ISBN 1-56792-147-7 OCLC 45080154

Further reading

- Scheurer, Timothy Due east., American Pop Music: The nineteenth century and Tin can Pan Alley, Bowling Green Land University, Popular Press, 1989 (Book I)

- Scheurer, Timothy E., American Pop Music: The age of rock" , Bowling Green State University, Popular Press, 1989 (Volume II)

External links [edit]

- Tin Pan Aisle American Popular Music Project

- Parlor Songs: History of Tin can Pan Alley

berlangadistaild68.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tin_Pan_Alley

0 Response to "What Kind of Performance Art Does Tin Pan Alley Perfor"

Post a Comment